Here are two examples to illustrate how to find the stationary distribution and how to use it.

10.4.1A Diffusion Model by Ehrenfest¶

Paul Ehrenfest proposed a number of models for the diffusion of gas particles, one of which we will study here.

The model says that there are two containers containing a total of particles. At each instant, a container is selected at random and a particle is selected at random independently of the container. Then the selected particle is placed in the selected container; if it was already in that container, it stays there.

Let be the number of particles in Container 1 at time . Then is a Markov chain with transition probabilities given by:

The chain is clearly irreducible. It is aperiodic because .

Question: What is the stationary distribution of the chain?

Answer: We have computers. So let’s first find the stationary distribution for particles, and then see if we can identify it for general .

N = 100

states = np.arange(N+1)

def transition_probs(i, j):

if j == i:

return 1/2

elif j == i+1:

return (N-i)/(2*N)

elif j == i-1:

return i/(2*N)

else:

return 0

ehrenfest = MarkovChain.from_transition_function(states, transition_probs)

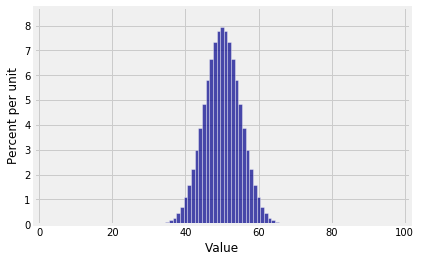

Plot(ehrenfest.steady_state(), edges=True)

That looks suspiciously like the binomial (100, 1/2) distribution. In fact it is the binomial (100, 1/2) distribution. Let’s solve the balance equations to prove this.

The balance equations are:

Now rewrite each equation to express all the elements of in terms of . You will get:

and so on by induction:

This is true for as well, since .

Therefore the stationary distribution is

In other words, the stationary distribution is proportional to the binomial coefficients. Now

So and the stationary distribution is binomial .

10.4.2Expected Reward¶

Suppose I run the sticky reflecting random walk from the previous section for a long time. As a reminder, here is its stationary distribution.

stationary = reflecting_walk.steady_state()

stationaryQuestion 1: Suppose that every time the chain is in state 4, I win 4 dollars; every time it’s in state 5, I win 5 dollars; otherwise I win nothing. What is my expected long run average reward?

Answer 1: In the long run, the chain is in steady state. So I expect that on 62.5% of the moves I will win nothing; on 25% of the moves I will win 4 dollars; and on 12.5% of the moves I will win 5 dollars. My expected long run average reward per move is 1.65 dollars.

0*0.625 + 4*0.25 + 5*.1251.625Question 2: Suppose that every time the chain is in state , I toss coins and record the number of heads. In the long run, how many heads do I expect to get on average per move?

Answer 2: Each time the chain is in state , I expect to get heads. When the chain is in steady state, the expected number of coins I toss at any given move is 3. So, by iterated expectations, the long run average number of heads I expect to get is 1.5.

stationary.ev()/21.5000000000000013If that seems artificial, consider this: Suppose I play the game above, and on every move I tell you the number of heads that I get but I don’t tell you which state the chain is in. I hide the underlying Markov Chain. If you try to recreate the sequence of steps that the Markov Chain took, you are working with a Hidden Markov Model. These are much used in pattern recognition, bioinformatics, and other fields.