The state space of a process is the set of possible values of the random variables in the process. We will often denote the state space by .

For example, consider a random walk where a gambler starts with a fortune of dollars for some positive integer , and bets on successive tosses of a fair coin. If the coin lands heads he gains a dollar, and if it lands tails he loses a dollar.

Let , and for let where is an i.i.d. sequence of increments, each taking the value +1 or -1 with chance . The state space of this random walk is the set of all integers. In this course we will restrict the state space to be discrete and typically finite.

🎥 See More

10.1.1Markov Property¶

Consider a stochastic process . The Markov property formalizes the idea that the future of the process depends only on where the process is at present, not on how it got there.

For each , the conditional distribution of given depends only on .

That is, for every sequence of possible values ,

The Markov property holds for the random walk described above. Given the gambler’s fortune at time , the distribution of his fortune at time doesn’t depend on his fortune before time . So the process is a Markov Chain representing the evolution of the gambler’s fortune over time.

Conditional Independence

Recall that two random variables and are independent if the conditional distribution of given is just the unconditional distribution of .

Random variables and are said to be conditionally independent given if the conditional distribution of given both and is just the conditional distribution of given alone. That is, if you know , then additional knowledge about doesn’t change your opinion about .

In a Markov Chain, if you define time to be the present, time to be the future, and times 0 through to be the past, then the Markov property says that the past and future are conditionally independent given the present.

10.1.2Initial Distribution and Transition Probabilities¶

Let be a Markov chain with state space . The distribution of is called the initial distribution of the chain.

A a trajectory or path is a sequence of states visited by the process. Let denote a path of finite length, with representing the value of . By the Markov property, the probability of this path is

The conditional probabilities in the product are called transition probabilities. For states and , the conditional probability is called a one-step transition probability at time .

10.1.3Stationary Transition Probabilities¶

For many chains such as the random walk, the one-step transition probabilities depend only on the states and , not on the time . For example, for the random walk,

for every . When one-step transition probabilites don’t depend on , they are called stationary or time-homogenous. All the Markov chains that we will study in this course have time-homogenous transition probabilities.

For such a chain, define the one-step transition probability

Then the probability of every path of finite length is the product of a term from the initial distribution and a sequence of one-step transition probabilities:

🎥 See More

10.1.4One-Step Transition Matrix¶

The one-step transition probabilities can be represented as elements of a matrix. This isn’t just for compactness of notation – it leads to a powerful theory.

The one-step transition matrix of the chain is the matrix whose th element is .

Often, is just called the transition matrix for short. Note two important properties:

is a square matrix: its rows as well as its columns are indexed by the state space.

Each row of is a distribution: for each state , and each , Row of the transition matrix is the conditional distribution of given that . Because each of its rows adds up to 1, is called a stochastic matrix.

Let’s see what the transition matrix looks like in an example.

10.1.5Sticky Reflecting Random Walk¶

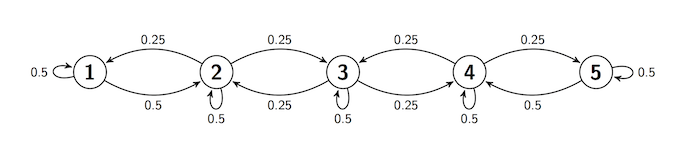

Often, the transition behavior of a Markov chain is easier to describe in a transition diagram instead of a matrix. Here is such a diagram for a chain on the states 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. The diagram shows the one-step transition probabilities.

No matter at which state the chain is, it stays there with chance 0.5.

If the chain is at states 2 through 4, it moves to each of its two adjacent state with chance 0.25.

If the chain is at states 1 or 5, it moves to its adjacent state with chance 0.5.

We say that there is reflection at states 1 and 5. The walk is sticky because of the positive chance of staying in place.

Transition diagrams are great for understanding the rules by which a chain moves. For calculations, however, the transition matrix is more helpful.

To start constructing the matrix, we set the array s to be the set of states and the transition function refl_walk_probs to take arguments and and return .

s = np.arange(1, 6)

def refl_walk_probs(i, j):

# staying in the same state

if i-j == 0:

return 0.5

# moving left or right

elif 2 <= i <= 4:

if abs(i-j) == 1:

return 0.25

else:

return 0

# moving right from 1

elif i == 1:

if j == 2:

return 0.5

else:

return 0

# moving left from 5

elif i == 5:

if j == 4:

return 0.5

else:

return 0You can use the prob140 library to construct MarkovChain objects. The from_transition_function method takes two arguments:

an array of the states

a transition function

and displays the one-step transition matrix of a MarkovChain object.

reflecting_walk = MarkovChain.from_transition_function(s, refl_walk_probs)

reflecting_walkCompare the transition matrix with the transition diagram, and confirm that they contain the same information about transition probabilities.

To find the chance that the chain moves to given that it is at , go to Row and pick out the probability in Column .

Answer

Both answers are 0.25

If you know the starting state, you can use to find the probability of any finite path. For example, given that the walk starts at 1, the probability that it then has the path [2, 2, 3, 4, 3] is

0.5 * 0.5 * 0.25 * 0.25 * 0.250.00390625The MarkovChain method prob_of_path saves you the trouble of doing the multiplication. It takes as its arguments the starting state and the rest of the path (in a list or array), and returns the probability of the path given the starting state.

reflecting_walk.prob_of_path(1, [2, 2, 3, 4, 3])0.00390625reflecting_walk.prob_of_path(1, [2, 2, 3, 4, 3, 5])0.0Answer

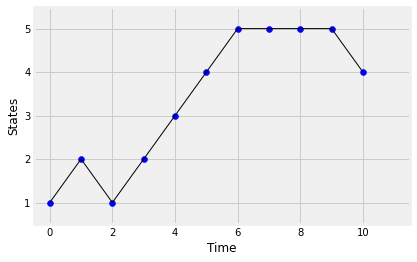

You can simulate paths of the chain using the simulate_path method. It takes two arguments: the starting state and the number of steps of the path. By default it returns an array consisting of the sequence of states in the path. The optional argument plot_path=True plots the simulated path. Run the cells below a few times and see how the output changes.

reflecting_walk.simulate_path(1, 7)array([1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 1])reflecting_walk.simulate_path(1, 10, plot_path=True)

🎥 See More

10.1.6-Step Transition Matrix¶

For states and , the chance of getting from to in steps is called the -step transition probability from to . Formally, the -step transition probability is

In this notation, the one-step transition probability can also be written as .

The -step transition probability can be represented as the th element of a matrix called the -step transition matrix. For each state , Row of the -step transition matrix contains the distribution of given that the chain starts at .

The MarkovChain method transition_matrix takes as its argument and displays the -step transition matrix. Here is the 2-step transition matrix of the reflecting walk defined earlier in this section.

reflecting_walk.transition_matrix(2)You can calculate the individual entries easily by hand. For example, the entry is the chance of going from state 1 to state 1 in 2 steps. There are two paths that make this happen:

[1, 1, 1]

[1, 2, 1]

Given that 1 is the starting state, the total chance of the two paths is .

Answer

Both answers are 0.0625

Because of the Markov property, the one-step transition probabilities are all you need to find the 2-step transition probabilities.

In general, we can find by conditioning on where the chain was at time 1.

That’s the th element of the matrix product . Thus the 2-step transition matrix of the chain is .

By induction, you can show that the -step transition matrix of the chain is . That is,

Here is a display of the 5-step transition matrix of the reflecting walk.

reflecting_walk.transition_matrix(5)This is a display, but to work with the matrix we have to represent it in a form that Python recognizes as a matrix. The method get_transition_matrix does this for us. It take the number of steps as its argument and returns the -step transition matrix as a NumPy matrix.

For the reflecting walk, we will start by extracting as the matrix refl_walk_P.

refl_walk_P = reflecting_walk.get_transition_matrix(1)

refl_walk_Parray([[0.5 , 0.5 , 0. , 0. , 0. ],

[0.25, 0.5 , 0.25, 0. , 0. ],

[0. , 0.25, 0.5 , 0.25, 0. ],

[0. , 0. , 0.25, 0.5 , 0.25],

[0. , 0. , 0. , 0.5 , 0.5 ]])Let’s check that the 5-step transition matrix displayed earlier is the same as . You can use np.linalg.matrix_power to raise a matrix to a non-negative integer power. The first argument is the matrix, the second is the power.

np.linalg.matrix_power(refl_walk_P, 5)array([[0.24609375, 0.41015625, 0.234375 , 0.08984375, 0.01953125],

[0.20507812, 0.36328125, 0.25 , 0.13671875, 0.04492188],

[0.1171875 , 0.25 , 0.265625 , 0.25 , 0.1171875 ],

[0.04492188, 0.13671875, 0.25 , 0.36328125, 0.20507812],

[0.01953125, 0.08984375, 0.234375 , 0.41015625, 0.24609375]])This is indeed the same as the matrix displayed by transition_matrix, though it is harder to read.

When we want to use in computations, we will use this matrix representation. For displays, transition_matrix is better.

10.1.7The Long Run¶

To understand the long run behavior of the chain, let be large and let’s examine the distribution of for each value of the starting state. That’s contained in the -step transition matrix .

Here is the display of for the reflecting walk, for , and 100. Keep your eyes on the rows of the matrices as changes.

reflecting_walk.transition_matrix(25)reflecting_walk.transition_matrix(50)reflecting_walk.transition_matrix(100)The rows of are all the same! That means that for the reflecting walk, the distribution at time 100 doesn’t depend on the starting state. The chain has forgotten where it started.

You can increase and see that the -step transition matrix stays the same. By time 100, this chain has reached stationarity.

Stationarity is a remarkable property of many Markov chains, and is the main topic of this chapter.

Answer

(i)