When the joint distribution of and is bivariate normal, the regression line of the previous section does even better than just being the best among all linear predictors of based on . In this section we will construct a bivariate normal pair from i.i.d. standard normal variables. In the next section, we will identify the main property of the regression line for bivariate normal .

The multivariate normal distribution is defined in terms of a mean vector and a covariance matrix. As you know, normalizing the covariance makes it is easier to interpret. You have shown in exercises that for jointly distributed random variables and the correlation between and is defined as

where is in standard units and is in standard units.

24.2.1Properties of Correlation¶

You showed all of these in exercises.

depends only on standard units and hence is a pure number with no units

If then is 1 or -1 according to whether the sign of is positive or negative.

We say that measures the linear association between and .

24.2.2Correlation as a Cosine¶

Rewrite the formula for correlation to see that

So the variance of is

Notice the parallel with the formula for the length of the sum of two vectors, with correlation playing the role of the cosine of the angle between two vectors. If the angle is 90 degrees, the the cosine is 0. This corresponds to correlation being zero and hence the random variables being uncorrelated.

Later in this section, we will visualize this idea in the case where the joint distribution of and is bivariate normal.

🎥 See More

🎥 See More

24.2.3Constructing the Standard Bivariate Normal¶

The goal is to construct and that have the multivariate normal distribution with mean vector and covariance matrix for some such that . We will say that and have the standard bivariate normal distribution with correlation .

Any bivariate normal vector is a linear transformation of an i.i.d. standard normal vector. Start with two i.i.d. standard normal random variables and . We will construct the required bivariate normal random vector as a linear transformation of the random vector .

First note that since all three of , , and must have mean 0, the linear transformation has no shift term. We just need to identify numbers , , , and such that

Taking and is a good start because it gives us the right first coordinate.

Since both and must have variance 1, the covariance of and is equal to the correlation. So, by the independence of and ,

So now we have

Since , the final condition is . So will work, and we have the following result.

Let be standard normal.

Let be standard normal, independent of .

Let .

Then and have the standard bivariate normal distribution with correlation .

It is also true that if and are standard bivariate normal with correlation , then there is a standard normal independent of such that . The proof is an exercise.

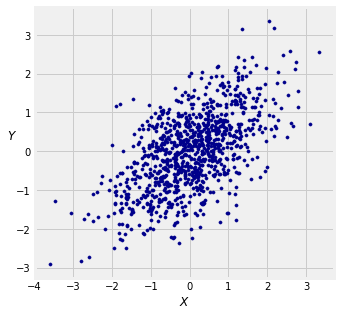

The graph below shows the empirical distribution of 1000 points in the case . You can change the value of and see how the scatter diagram changes. It will remind you of numerous such simulations in Data 8.

# Plotting parameters

plt.figure(figsize=(5, 5))

plt.axes().set_aspect('equal')

plt.xlabel('$X$')

plt.ylabel('$Y$', rotation=0)

plt.xticks(np.arange(-4, 4.1))

plt.yticks(np.arange(-4, 4.1))

# X, Z, and Y

x = stats.norm.rvs(0, 1, size=1000)

z = stats.norm.rvs(0, 1, size=1000)

rho = 0.6

y = rho*x + np.sqrt((1-rho**2))*z

plt.scatter(x, y, color='darkblue', s=10);

24.2.4Representations of the Bivariate Normal¶

When we are working with just two variables and , matrix representations are usually unnecessary. We will use the following three representations interchangeably.

and are bivariate normal with parameters

The standardized variables and are standard bivariate normal with correlation . Then for some standard normal that is independent of . This follows from Definition 2 of the multivariate normal.

and have the multivariate normal distribution with mean vector and covariance matrix

24.2.5Standard Bivariate Normal: Matrix Approach¶

In lab, you used a matrix approach to constructing standard bivariate normal and with correlation . Here is a summary of the construction. The end result is the same as what we developed above.

Let and be independent standard normal variables, that is, bivariate normal random variables with mean vector and covariance matrix equal to the identity. Now fix a number (that’s the Greek letter rho, the lower case r) so that , and let

Define a new random variable , and notice that

So and have the bivariate normal distribution with mean vector and covariance matrix

24.2.6Correlation as a Cosine: Geometry in the Bivariate Normal Case¶

We have defined

where and are i.i.d. standard normal.

Let’s understand this construction geometrically. A good place to start is the joint density of and , which has circular symmetry.

The and axes are orthogonal. Let’s see what happens if we twist them.

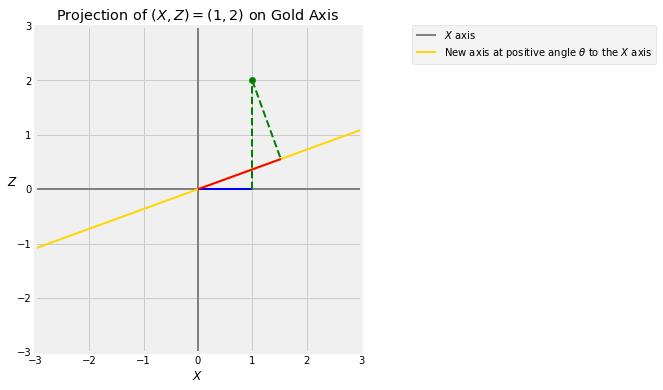

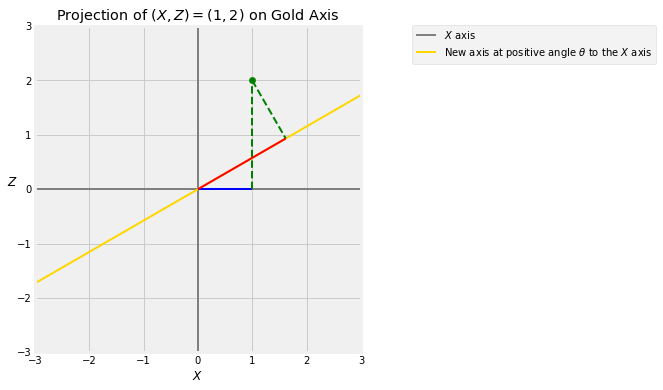

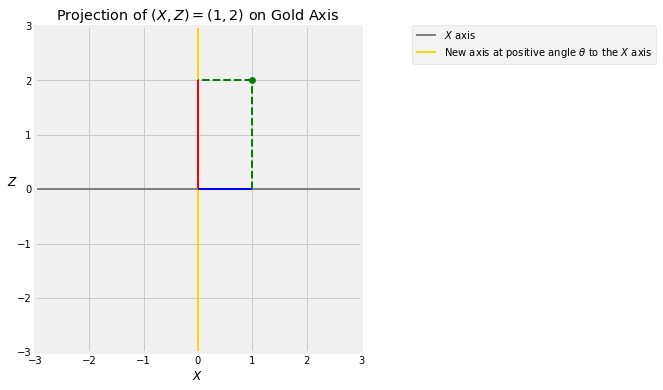

Take any positive angle degrees and draw a new axis at angle to the original axis. Every point has a projection onto this axis.

The figure below shows the projection of the point onto the gold axis which is at an angle of degrees to the axis. The blue segment is the value of . You get that by dropping the perpendicular from to the horizontal axis. That’s called projecting onto the horizontal axis.

The red segment is the projection of onto the gold axes, obtained by dropping the perpendicular from to the gold axis.

Vary the values of in the cell below to see how the projection changes as the gold axis rotates.

theta = 20

projection_1_2(theta)

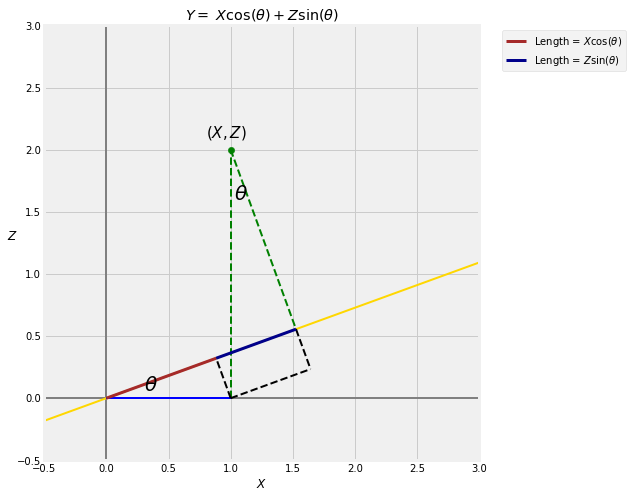

Let be the length of the red segment, and remember that is the length of the blue segment. When is very small, is almost equal to . When approaches 90 degrees, is almost equal to .

A little trigonometry shows that .

projection_trig()

Thus

where .

The sequence of graphs below illustrates the transformation for degrees.

theta = 30

projection_1_2(theta)

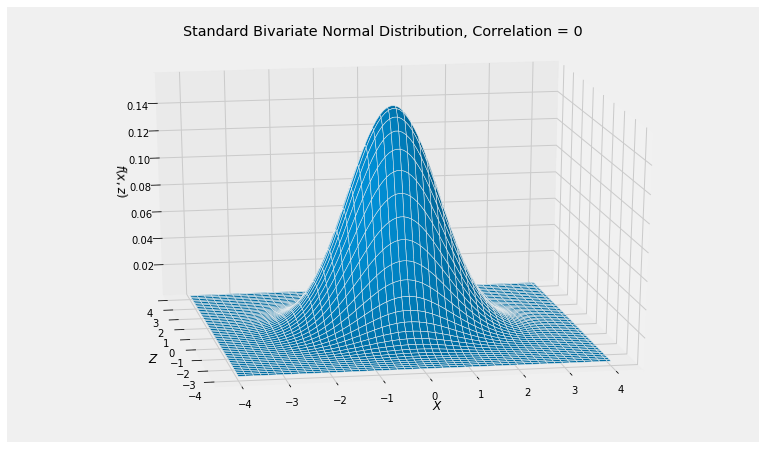

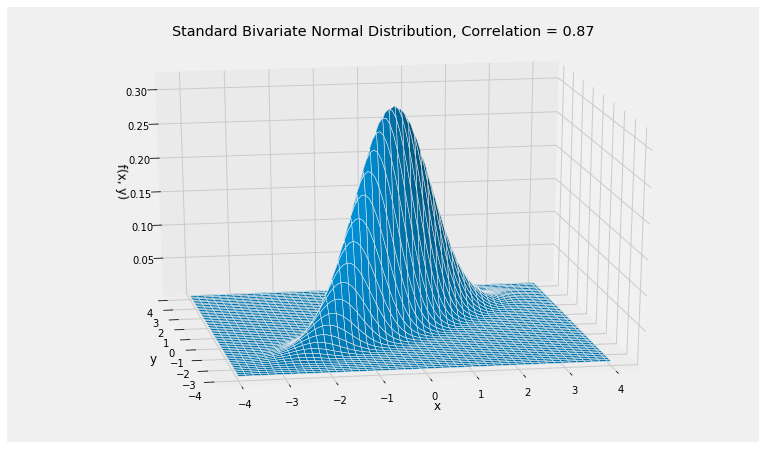

The bivariate normal distribution is the joint distribution of the blue and red lengths and when the original point has i.i.d. standard normal coordinates. This transforms the circular contours of the joint density surface of into the elliptical contours of the joint density surface of .

cos(theta), (3**0.5)/2(0.8660254037844387, 0.8660254037844386)rho = cos(theta)

Plot_bivariate_normal([0, 0], [[1, rho], [rho, 1]])

plt.title('Standard Bivariate Normal Distribution, Correlation = '+str(round(rho, 2)));

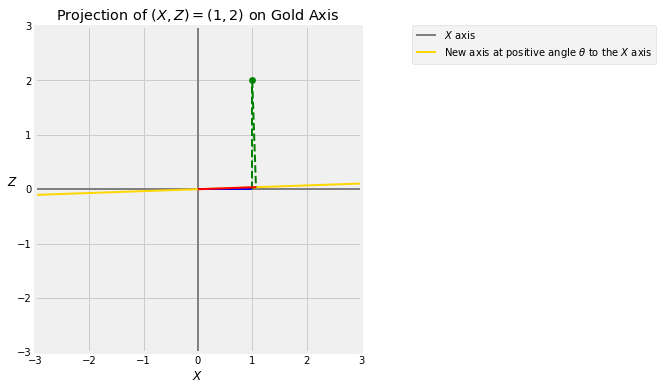

24.2.7Small ¶

As we observed earlier, when is very small there is hardly any change in the position of the axis. So and are almost equal.

theta = 2

projection_1_2(theta)

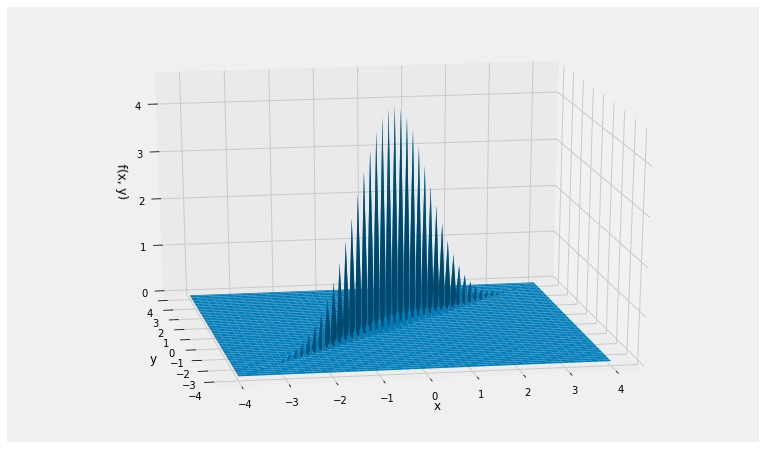

The bivariate normal density of and , therefore, is essentially confined to the line. The correlation is large because is small; it is more than 0.999.

You can see the plotting function having trouble rendering this joint density surface.

rho = cos(theta)

rho0.99939082701909576Plot_bivariate_normal([0, 0], [[1, rho], [rho, 1]])

24.2.8Orthogonality and Independence¶

When is 90 degrees, the gold axis is orthogonal to the axis and is equal to which is independent of .

theta = 90

projection_1_2(theta)

When degrees, . The joint density surface of is the same as that of and has circular symmetry.

If you think of as a “signal” and as “noise”, then can be thought of as an observation whose value is “signal plus noise”. In the rest of the chapter we will see if we can separate the signal from the noise.