Binomial probabilities involve powers and factorials, both of which are difficult to compute when is large. This section is about simplifying the computation of the entire distribution. The result also helps us understand the shape of binomial histograms.

🎥 See More

6.5.1Consecutive Odds Ratios¶

Fix and , and let be the binomial probability of . That is, let be the chance of getting successes in independent trials with probability of success on each trial.

The idea is to start at the left end of the distribution, with the term

Then we will build up the distribution recursively from left to right, one possible value at a time.

To do this, we have to know how the probabilities of consecutive values are related to each other. For , define the th consecutive odds ratio

These ratios help us calculate recursively.

and so on.

Even though we already have a formula for the binomial probabilities, building the distribution using consecutive ratios is better computationally and also helps us understand the shape of the distribution.

🎥 See More

6.5.2Binomial Consecutive Odds Ratios¶

How is this more illuminating than plugging into the binomial formula? To see this, fix and calculate the ratio .

Notice that the formulas for are simple. This makes it easy to compute recursively. For example, if , we can compute as

Answer

Multiply by to get 0.05844381950532852.

6.5.3Shapes of Binomial Histograms¶

Now observe that comparing to 1 tells us whether the histogram is going up, staying level, or going down at .

Note also that the form

tells us the the ratios are a decreasing function of . In the formula, and are the parameters of the distribution and hence constant. It is that varies, and appears in the denominator.

This implies that once for some , it will remain less than 1 for all larger . In other words, once the histogram starts going down, it will keep going down. It cannot come back up again.

That is why binomial histograms are either non-increasing or non-decreasing, or they go up and come down. But they can’t look like waves on the seashore. They can’t go up, come down, and go up again.

🎥 See More

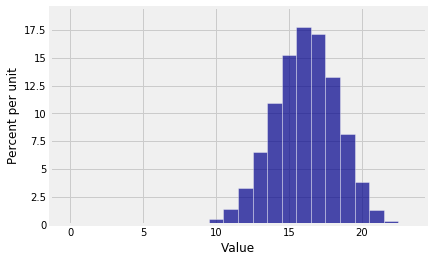

Let’s visualize this for a and , two parameters that have no significance other than being our choice to use in this example.

n = 23

p = 0.7

k = range(n+1)

bin_23_7 = stats.binom.pmf(k, n, p)

bin_dist = Table().values(k).probabilities(bin_23_7)

Plot(bin_dist)

# It is important to define k as an array here,

# so you can do array operations

# to find all the ratios at once.

k = np.arange(1, n+1, 1)

((n - k + 1)/k)*(p/(1-p))array([53.66666667, 25.66666667, 16.33333333, 11.66666667, 8.86666667,

7. , 5.66666667, 4.66666667, 3.88888889, 3.26666667,

2.75757576, 2.33333333, 1.97435897, 1.66666667, 1.4 ,

1.16666667, 0.96078431, 0.77777778, 0.61403509, 0.46666667,

0.33333333, 0.21212121, 0.10144928])What Python is helpfully telling us is that the invisible bar at 1 is 53.666... times larger than the even more invisible bar at 0. The ratios decrease after that but they are still bigger than 1 through . The histogram rises till it reaches its peak at . You can see that . Then the ratios drop below one, so the histogram starts going down.

6.5.4Mode of the Binomial¶

A mode of a discrete distribution is a possible value that has the highest probability. There may be more than one such value, so there may be more than one mode.

We have seen that once the ratio drops below 1, it stays below 1, so the histogram keeps falling. To identify the mode, therefore, we will find all values of such that .

Let . Every value for which must satisfy

That is,

which is equivalent to

We have shown that for all in the range 0 through the integer part of , the histogram rises; for larger , it falls.

Therefore the peak of the histogram is at the largest in this range. That’s the integer part of .

So the integer part of is a mode of the binomial.

Because the odds ratios are non-decreasing in , the only way in which there can be more than one mode is if there is a such that . In that case, and therefore both and will be modes. To summarize:

The mode of the binomial distribution is the integer part of . If is an integer, then is also a mode.

To see that this is consistent with what we observed in our numerical example above, let’s calculate in that case.

(n+1) * p16.799999999999997The integer part of is 16, which is the mode that we observed.

But in fact, is a more natural quantity to calculate. For example, if you are counting the number of heads in 100 tosses of a coin, then the distribution is binomial and you naturally expect heads. You don’t want to be worrying about .

In fact you don’t have to worry when is large, because then and are pretty close. In a later section we will examine a situation in which you can use to get an approximation to the shape of the binomial distribution when is large.