If is discrete, and is a monotone function, then finding the distribution of the random variable is straightforward: convert each possible value of by applying and leave the probabilities alone.

For example, if is uniform on the three values , and , then the you can just augment the distribution table of by the possible values of :

| 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| chance |

The new random variable is uniform on the three values .

But if has a density then both and have a continuum of values and we have to be more careful.

The method we developed in the previous section for finding the density of a linear function of a random variable can be extended to non-linear functions.

🎥 See More

16.2.1Change of Variable Formula for Density: Increasing Function¶

The function is differentiable and increasing. We will now develop a general method for finding the density of such a function applied to any random variable that has a density.

Let have density . Let be a smooth (that is, differentiable) increasing function, and let . Examples of such functions are:

for some . This case was covered in the previous section.

on positive values of

To develop a formula for the density of in terms of and , we will start with the cdf as we did above.

Let be smooth and increasing, and let . We want a formula for . We will start by finding a formula for the cdf of in terms of and the cdf of .

Now we can differentiate to find the density of . By the chain rule and the fact that the derivative of an inverse is the reciprocal of the derivative,

16.2.1.1The Formula¶

Let be a differentiable, increasing function. The density of is given by

16.2.2Understanding the Formula¶

To see what is going on in the calculation, we will follow the same process as we used for linear functions in an earlier section.

For to be , has to be .

Since need not be linear, the tranformation by won’t necessarily stretch the horizontal axis by a constant factor. Instead, the factor has different values at each . If denotes the derivative of , then the stretch factor at is , the rate of change of at . To make the total area under the density equal to 1, we have to compensate by dividing by . This is valid because is increasing and hence is positive.

This gives us an intuitive justification for the formula.

16.2.3Applying the Formula¶

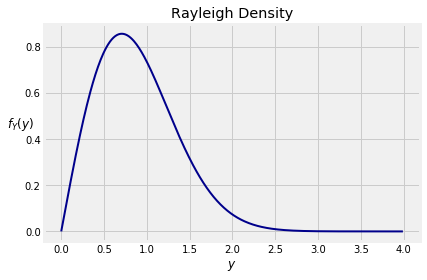

Let have the exponential (1/2) density and let . We can take the square root because is a positive random variable.

Let’s find the density of by applying the formula we have derived above. We will organize our calculation in four preliminary steps, and then plug into the formula.

The density of the original random variable: The density of is for .

The function being applied to the original random variable: Take . Then is increasing and its possible values are .

The inverse function: Let . We will now write in terms of , to get .

The derviative: The derivative of is given by .

We are ready to plug this into our formula. Keep in mind that the possible values of are . For the formula says

So for ,

This is called the Rayleigh density. Its graph is shown below.

Answer

Exponential

16.2.4Change of Variable Formula for Density: Monotone Function¶

Let be smooth and monotone (that is, either increasing or decreasing). The density of is given by

We have proved the result for increasing . When is decreasing, the proof is analogous to proof in the linear case and accounts for being negative. We won’t take the time to write it out.

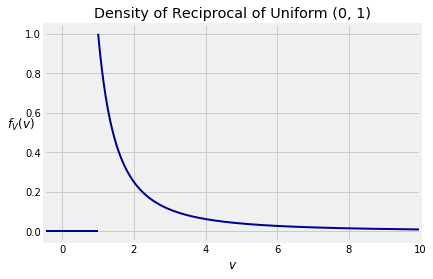

16.2.4.1Reciprocal of a Uniform Variable¶

Let be uniform on and let . The distribution of is called the inverse uniform but the word “inverse” is confusing in the context of change of variable. So we will simply call the reciprocal of .

To find the density of , start by noticing that the possible values of are in as the possible values of are in .

The components of the change of variable formula for densities:

The original density: for .

The function: Define .

The inverse function: Let . Then .

The derivative: Then .

By the formula, for we have

That is, for ,

So

You should check that is indeed a density, that is, it integrates to 1. You should also check that the expectation of is infinite.

The density belongs to the Pareto family of densities, much used in economics.